Since I was a kid, the stars and planets have fascinated me. I imagine that holds true for many kids. Like many other kids, I am sure, I looked through toy telescopes and was less than impressed. Even when I went to a real observatory I was not that impressed as we got a quick look after an hour of waiting. Even though I was impressed with all things space-related I really could not find a way to participate in it until much later in life.

I found myself able to use a fairly nice amateur telescope and had some fun. I have always had an interest in photography, mainly the technical side, so I wanted to pair that with my new abilities in astronomy. Astrophotography seemed like just the right hobby, but it could be really expensive. I needed to do some research.

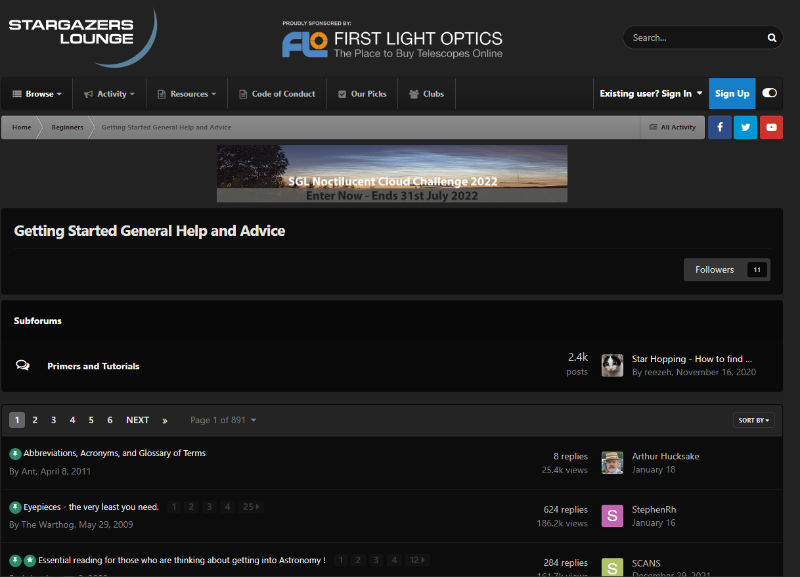

I visited some forums including Cloudy Nights (best for technical issues and advanced imagers) and Stargazer’s Lounge (better for beginners), both excellent and full of knowledge. Pouring over the posts there I was just overwhelmed. The more I read, the more I didn’t understand, and I could just not see a way forward without just throwing money at it and seeing what stuck. My bank account just said no.

Then someone on one of the forums seemed to see my problem and suggested that I try a book instead of just trying to piece everything together myself. That sounded like an excellent idea, but astronomy books I had seen were way over my head and/or didn’t cover astrophotography, particularly for the absolute beginner.

One day while searching around I found a listing for books titled The Five Best Books on Astrophotography I know, I normally don’t ever stop for any articles that have any wording like “the five best” in the title because they can be just trying to sell you something and have never actually used the items. What can I say, I was desperate.

Looking at the list I went to Amazon for each one and read the description and reviews for each one. I was initially intrigued by the fact that there were two books on the list by the same author. I checked the reviews, they seemed good, and I really liked the fact that both books seemed to be pointed right at the person starting from scratch. I decided to get one and see if it was any good.

I wound up purchasing Getting Started: Long Exposure Astrophotography by Allan Hall. I have to admit, I was impressed. It was an older book but was exactly what I needed. It assumed I knew basically that I wanted to take pictures of stuff in space, and nothing else, it started with the basics and built from there. It was much more like talking to a friend over pizza and beer than a technical manual, and I really liked that.

One of the other things that drew me to this particular title was the fact that the author has published a slew of related books, a pretty extensive astronomy and astrophotography website, a reasonable YouTube channel, and has even started a Gskyer Telescope Manual website for people who purchased those really cheap telescopes and don’t know how to use them. This made me believe that whatever direction my interest took, I could find information from the same source and I found comfort in that.

There was some research to be done as parts of the book covered hardware and software that was outdated. Fortunately, that was the easy part. It turns out that even if a piece of software is really old, there is usually an update, and telescopes always have something comparable on the market even if you have to switch brands.

It did take me some time, no doubt, there is a lot to learn. There is also a lot of equipment to get working together. I just approached it the same way the book did, step by step.

Once I started getting images, the excitement grew. The really awesome part about this for me was to see the improvement almost every time I went out. I learned that this was just as much an art as it was a science, and that fits my personality just right. There was a basic formula that would get you into the ballpark, but then it was up to you to find what worked best for your equipment, time, imaging location, and abilities.

One can get started in this hobby with nothing more than a DSLR equivalent camera, or an inexpensive telescope and your phone’s camera. From there, the sky is the limit, pun intended. I did spend a little more money than I wanted initially, but I think I got a pretty good system that will last me for a really long time. Something I can really grow into.

I think that is probably the way to go as it allows you to concentrate more on learning what works and how you should approach things instead of constantly fighting with your hardware.

The art of astrophotography

Once I got the technical basics under my belt I was free to express a little more artistic flair in my images. You see, once you have captured the data for the images you need to meld all that data together, stretch it, massage it, and knead it into a form that matches your inner vision. If this sounds like you are just creating a bunch of photoshopped images that have little basis in reality, well, that is partially true.

You see, very little in outer space is actually very interesting to the naked eye. Things like nebulae are either not visible at all, or are in a spectrum of light that our eye is just not very sensitive to. This means that all the cool images you see by NASA, and everything in Sky and Telescope magazine, it is all “fictionalized” in image processing software so that you can see them.

This doesn’t mean there is no basis in fact, it just means that where your eye might see a little smudge of gray cloudiness representing the North American nebula, an image taken of it with 50 frames at 10 minutes of exposure per frame, then stacked, stretched, and manipulated will show a bright red nebula showing an immense amount of detail roughly in the shape of the North American continent.

Technically, the nebula is emitting light from Hydrogen-Alpha which is in the red part of the light spectrum, but in such small quantities that you would never be able to see the red even if you were literally inside the nebula, in a spaceship, looking out the window.

I feel this is more an intensification rather than a falsification as the colors you are bringing out are really there in some form, you are just making them stronger, more vibrant. We do the same things to images all the time. No bride really looks as good in person as in her wedding pictures.

This is where you get to use your artistic side. What shade of blue is the Iris Nebula and how bright is it? Is the Rosette more towards pink or dark red? How far do you stretch the Lyre dark nebula to show that it really is there? There is no wrong or right answer to these questions, it is all up to you. The image processing software gives you the tools to make this happen.

There are many types of astrophotography, I chose what some call long exposure astrophotography. This is for very dim objects like nebulae. Earlier I mentioned you might be working with 50 images, each with an exposure time of 10 minutes. That works out to 500 minutes plus another 120 of setup and tear down time so let’s say about 620 minutes or just under ten and a half hours. Most of that time you will spend just waiting on the camera and telescope to do their thing, this is where the zen comes in.

The zen of astrophotography

When you have huge stretches of time with little to do but wait, all under clear dark skies, you tend to spend a lot of time sitting there looking up.

At first, you might spend that time reading, looking at different targets, or checking them out with binoculars or a second telescope. That is how it started for me anyway. Eventually, that led to me just looking up with my eyes, taking it in, and seeing the beauty that had always been there and therefore hidden.

That sounds like a cheap fortune cookie but it is true. Think about your home town, then really try and think about it from the point of view of a tourist who has never been there before. What would they see? My own personal observations are that there are a lot of things in my small town I take for granted, that I pass every day and never really see for how interesting they really are. It is because I am there, seeing it all the time, that it becomes part of the background.

The stars were no different for me, they were just background noise for what I was really after. That is until they became what I was looking at because I had nothing else to do. They became the front and center of my interest. Once there, they were simply amazing.

I read an article from that same author whose book I bought talking about how he was out imaging one night and the clouds started rolling in. Instead of getting upset he just sat there, staring at the clouds, smiling. For the first time in a long time, he could actually see the clouds for how amazing they were and really appreciate them. I can completely get on board with that.

Once I stopped and just looked, no phone, no camera, no binoculars, no star map, nothing, just looking, the result could absolutely be called zen.